In April 1768, while traveling to the Moravian mission settlement of Friedenshütten on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River, Johannes Ettwein not only kept a written journal of his route,[1] but also recorded the trip on a hand-drawn map (see Figure 1). The map he drew, based on his own observations and, of course, without the aid of satellite technology or other modern mapping tools, is remarkably accurate. Joining the river at the present-day site of Forty Fort, Ettwein followed the North Branch of the Susquehanna River along its winding curves up to the village of Friedenshütten near Wyalusing. Along the route Ettwein noted down botanical information, especially that which might be useful for medicinal purposes; he also recorded settlements of both White and Native peoples, islands in the river, steep cliffs on the side, and riffles and rapids in the water.

What might at first glance appear to be an occasional sketch of interest to local historians and enthusiasts of the river is, however, of importance in understanding Moravian concepts of space and its mapping in the 18th century. In a previous article, Ettwein’s sketch of the Friedenshütten site was shown to have been used as a draft for the far more elaborate and detailed manuscript map drawn by Golkowsky.[2] Although this present pen and ink map is far more modest and was not further elaborated upon by the Moravians, it serves as an excellent example of the observations and recordings of one of the most influential American Moravians in the 18th century.

Kept in the Unity Archives in Herrnhut, Germany, the map is catalogued as “Indianer Mission. Oberlauf des Susquehanna von Friedenshütten bis Wyomik. Herrnhut, R 14A. No. 48.” Originally oriented East to West, (based on the handwriting in the compass), the map reflects the experience of travelling up the Susquehanna along this stretch as an ascent, moving higher into the Endless Mountains of North-Eastern Pennsylvania. Making this map available to a wider audience allows us, to some degree, to map the experience of so many Moravian men and women in the mission field of North America as they traversed the mountains, rivers, and streams of this part of North America. Linking the map with Ettwein’s own account also allows us to see how the author made choices of information to include in the written account versus the cartographic one. The spatialization of Ettwein’s account of his trip reveals the differing intentions of journal and map: the former tells a narrative of dangerous currents, rocky trails, the history of both Native and white peoples, and fortuitous meetings with knowledgeable guides; the latter reveals awareness of the terrain, flora, and the flows of the river.

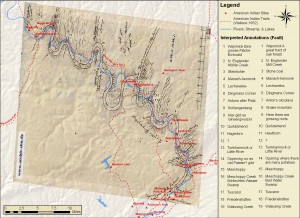

It is perhaps a truism to say that we map what we see, but this is important in understanding why Ettwein chose to record those particular sights and places on this map. In order to elucidate his vision, Ettwein’s map was used as a base in the creation of a multi-layered map of the same stretch of the river that showed the hydrological data (the river, larger lakes, and some creeks), the topography, the major Indian paths,[3] and also the locations of major Native American settlements of the contact period, drawn from archaeological and scholarly accounts of the area. Using GIS (geographical information systems) and ArcMap, Bucknell University senior Emily Bitely, ’11 superimposed these layers one on another and added a key to the places noted by Ettwein to the composite map (see Figure 2). A scale bar was also added to aid with orientation. The author added translations of the annotations. (Katherine Faull)

[1] The account of his journey was translated and published 100 years ago along with documents that pertained to David Zeisberger’s mission activity in Ohio. See, “Report of journey of John Ettwein, David Zeisberger and Gottlob Sensemann to Friedenshütten and their stay there in 1768” in The Diaries of Zeisberger relating to the first missions in the Ohio Basin, ed. A. B. Hulbert and W.N. Schwartze, Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society Publications XXI (Jan.) 1912, pp. 32-42. The Moravian Records, vol II.

[2] See Katherine Faull, “Mapping a Mission: The Origins of Golkowski’s 1768 Map of Friedenshütten, Pennsylvania” JMH 7 (2009): 107-116

[3] Paul Wallace, Indian Paths of Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1998).