In November 2009, a team of faculty and students (undergraduate and graduate) from Bucknell University, Bloomsburg, and SUNY Buffalo submitted a 100-page report on the feasibility of having the Susquehanna River included as a connector trail for the John Smith Trail. Funded by the Conservation Fund/R.K. Mellon Foundation, the universities partnered with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Eastern Delaware Nations, the Susquehanna Greenway Partnership and the Pennsylvania Environmental Council to make an argument for the river being designated as a connector trail to the Historic John Smith trail. We cite the Executive Summary:

“Basing its conclusions on detailed investigation of the history of Native American settlement along the River, archaeological evidence, natural history of the River, and the cultural significance of the river to contemporary Native Americans, the team concludes that the Susquehanna met all three criteria:

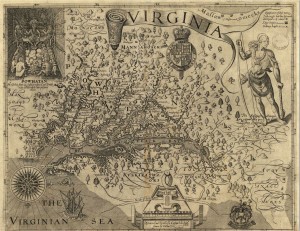

- The Susquehanna River shows a close association with Smith’s actual voyages, in termsof his travel to the mouth of the Susquehanna and direct important exchanges with the Susquehannock Indians who inhabited the river corridor, and his mapping of Indian sites along the Susquehanna; (Criterion A substantive)

- The river corridor shows a strong connection with 17th-century Native American peoples known to; John Smith (Criterion B substantive)

- It also remains importantly illustrative of the natural history of the 17th centuryChesapeake Bay Watershed, both in terms of existing landscapes and habitats and itsintegral ongoing connection as the largest source of the Chesapeake, which is in effect geologically an ancient section of the Susquehanna Valley (Criterion C substantive)

In our view, the above associations also require that the river be treated holistically for designation, as a historical environmental-and-cultural system, focusing on its main corridor from the existing John Smith Trail near the Chesapeake to the Susquehanna headwaters at Lake Otsego. Traveling this system in the context of the John Smith Trail involves dynamically traveling through layers of time and nature, given the river corridor’s connections with the peoples directly encountered and mapped by John Smith, in their dynamic interactions with one another before and during his era, and with Euro-American movement into the watershed following Smith. In this sense, designation of the main corridor as a connector trail not only reflects historic and environmental links of northern “Iroquoia” to the realms of the Susquehannocks experienced by Smith, but also provides a needed cultural corrective to potential Eurocentric focus of the Smith Trail. Its name would likely derive from indigenous language and it would link the Smith Trail directly with living Iroquois and Eastern Delaware peoples who mainly live in and engage with the upper watershed and who historically incorporated remnants of the Susquehannocks. It also would preserve and re-present historic perspectives of native peoples looking out from the heart of the Eastern Woodlands to meet and encounter Smith and his people down river as they in turn came up the Chesapeake.

Finally, in terms of the third criterion, the Susquehanna watershed remains a living system integrally related to the Chesapeake, preserving on large stretches glimpses of scenery experienced by kayak and land sojourners today as evocative of pre-settlement and early settlement landscape and natural history connected with Smith’s experience. We find significant segments to be eminently interpretable, preservable and (in part) restorable. Considering the Chesapeake-Susquehanna network as a whole in designation would support integrated recreational, educational and environmental opportunities while avoiding older Eurocentric paradigms. This would provide more authentic engagement with indigenous holistic perspectives on space and natural systems evident from Smith’s era and subsequent reports (what one historian described as a fluid “archipelago” of native communities on the Susquehanna), in line also with new scholarly emphases on the continuum of nature and culture in environmental systems (as in models of environmental semiospheres in biosemiotics).

In short, designation of the main Susquehanna corridor would serve as deserved tribute to the larger networks of both Native American cultures and natural environments that engaged in direct exchange with John Smith and Anglo culture in the sixteenth century, in a foundational era and region for America, while providing incredible opportunities for environmental, community and cultural synergy and restoration in the Susquehanna-Chesapeake complex today. Such designation also would enable the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, probably the largest organization of historic Native American governments in the northeastern U.S., and representing the cultures from which the Susquehannock communities that Smith knew had emerged and to whom their remnants later returned, to join as direct partners with the National Park Service in the John Smith Chesapeake Trail network.

As a man with Susquehannock ancestry, living today in the proposed Susquehanna connector trail corridor in Pennsylvania, put it to one of our researchers regarding his cultural connections to the river: “You know, in the native way of thinking, something that has movement is alive, and if it’s alive then it is a spiritual being.That includes not just animals and birds and things, but also the river. I grew up along the Susquehanna River. My grandmother, who taught me most of what I know about being native, always used to say to me, ‘That river is you. Without that river, our people would not be who they are.’ So it is important to care for the river for the Seven Generations to come.”

John_Smith_Connector_Trail_Report