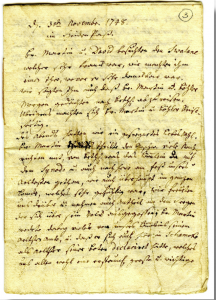

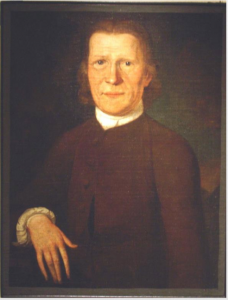

In 2009 the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded Professor Katherine Faull a collaborative research grant ($116,000) to translate, edit and disseminate the vitally important manuscripts that constitute the Moravian mission diary of the strategic Native American “capital” of the 18th century woodlands Indians at Shamokin, Pennsylvania (today, Sunbury). This collection of manuscripts (written primarily in German with a few sections in English) was written by 10 different missionaries, including the young David Zeisberger, perhaps the most famous observer of Native American life before John Heckewelder (whose work acted as a source for Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales).

In 2009 the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded Professor Katherine Faull a collaborative research grant ($116,000) to translate, edit and disseminate the vitally important manuscripts that constitute the Moravian mission diary of the strategic Native American “capital” of the 18th century woodlands Indians at Shamokin, Pennsylvania (today, Sunbury). This collection of manuscripts (written primarily in German with a few sections in English) was written by 10 different missionaries, including the young David Zeisberger, perhaps the most famous observer of Native American life before John Heckewelder (whose work acted as a source for Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales).

The importance of the Moravian mission diary to studies of Colonial history, ethnography, missiology, and micro-histories of specific communities has recently become paramount in the re-examination of the relationship between ethnography and missiology, and of course within the field of Native American Studies. Such translations of mission communities have made available to scholars as yet untapped primary sources on the contact period in North America. However, the Shamokin Moravian diary differs substantially from these published mission diaries in that Shamokin itself was not a mission settlement built by the Moravians but rather pre-existed their advent by several centuries, first as a Susquehannock, then Shawnee, and then in the early 18th century as a primarily Delaware settlement and trading post, overseen by the Iroquois vice-regent, the Oneida Chief Shikellamy.

In addition, for this area of Central Pennsylvania, the lack of access to primary historical sources from the time of initial contact through the colonial period has led to an overly heavy reliance on a few 19th and 20th century interpretations of 18th century primary sources that have colored the presentation of this fascinating hub of human exchange through their contemporary cultural biases. Unlike human settlements at other confluences, the settlement of Shamokin has received only superficial attention either from historians of culture, Colonial history or ethnographers. The literature that does exist on the settlement reverberates with the dark judgment passed on the place nearly 250 years ago that dubbed it the seat of “the prince of darkness.” Only very recently, through meticulous and intelligent reading of mission reports composed in archaic German script have historians challenged the perception of a polarized population of Native Americans and Europeans in the upper reaches of the Susquehanna River.

The dominant view of Shamokin, promoted by historians for at least a century, has been that it was a place of darkness and magic. However, the diaries reveal a far more complex picture of political and cultural negotiation, a confluence of cultures, and environmental epistemology. It describes the missionaries’ regular visits to the settlements of Delaware women on Packer’s Island, regular suppers with Shikellamy in their log home, trips up and down the Susquehanna river to speak with the men of the Delaware who were back from hunting, visits from the envoys of the Six Nations on their way to and from important political meetings with the Colonial administration in Lancaster and Philadelphia, as well as an environmental diary of natural events such as an earthquake, floods, famine, planting, and harvesting.

The Shamokin diary provides not only a wealth of information about the cultural interactions, historical events, and spiritual condition of the settlement in the years 1745-1755, it also offers a “local earth story” about the ecology, climate, and geography of the area in the mid-1700s. Repeatedly, the diarists record high waters of the Susquehanna, the ice jams, the bitter cold of winter that drives the Delaware men back to the settlement from their hunting expeditions, the planting of indigenous crops of corn, squash and beans, and the revival of the peach and apple orchards planted by earlier European visitors. Frequently, there is much hunger around Shamokin, a dearth of good seed to plant, but also the occasional shared feast of venison or bison meat.