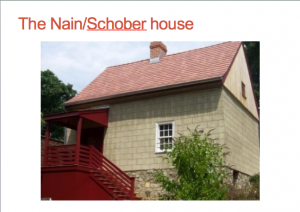

In September, 2012, Professor Faull was invited to speak on the occasion of the rededication of he Nain Indian House in Bethlehem, Pa. The history behind the modest cottage on Heckewelder Place in the historical downtown of Bethlehem provides us with the opportunity to examine the beginnings of Moravian mission activity in Pennsylvania and to follow the odyssey of the Moravian Indians from the Lehigh Valley, to Philadelphia, then up to Friedenshütten on the North Branch of the Susquehanna before their departure to the ill-fated mission in Ohio.

Thank you for the invitation to speak at this significant event that marks the culmination of decades’ worth of work to restore the Nain house. The perseverance and vision of those who have worked to achieve this vision should be noted and rewarded! I would like to speak today about how the physical restoration of the Nain Indian house is not only an achievement for Historic Bethlehem, but also represents an significant moment in the interpretation and representation of the history of Moravian Bethlehem. I will argue that this modest house offers the world of scholars, historians, archivists, and interpreters of Moravian heritage an opportunity to present a new picture of Bethlehem, one that moves beyond the realm of sugar cake and Moravian stars to an interpretive history that reveals the best of Moravian intentions and one of the darkest moments in the era of the founding of the American Republic.

This house, as many of you may know, was sold to “Bethlehem individuals” in March 1765, after the decision had been made to move the Moravian Indians from Nain and nearby Wechquetank to the Upper North Branch of the Susquehanna River, a place that had been traditionally settled by Delaware and Mohican Indians, Machwihilusing. The abandonment of the Nain village, most recently discussed by Kate Carté Engle in the Journal of Moravian History, stems from the decision made at the 1765 Bethlehem conference that focused on the future of the Nain Indians. It was at this conference, Engel argues, that the growing rift between decisions made in Herrnhut and the political realities of Bethlehem during the turmoil of the French Indian war became clear. The end of Nain , argues Engel, signifies the end of the original mission of Bethlehem that was set out by Zinzendorf in 1742.

This house, as many of you may know, was sold to “Bethlehem individuals” in March 1765, after the decision had been made to move the Moravian Indians from Nain and nearby Wechquetank to the Upper North Branch of the Susquehanna River, a place that had been traditionally settled by Delaware and Mohican Indians, Machwihilusing. The abandonment of the Nain village, most recently discussed by Kate Carté Engle in the Journal of Moravian History, stems from the decision made at the 1765 Bethlehem conference that focused on the future of the Nain Indians. It was at this conference, Engel argues, that the growing rift between decisions made in Herrnhut and the political realities of Bethlehem during the turmoil of the French Indian war became clear. The end of Nain , argues Engel, signifies the end of the original mission of Bethlehem that was set out by Zinzendorf in 1742.

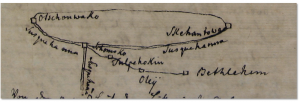

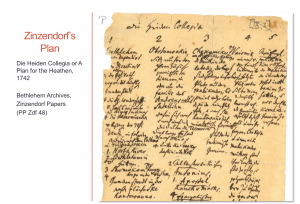

So, what was Zinzendorf’s original plan? In a document entitled “Heiden Collegia” housed at the Moravian Archives in Bethlehem we can see the leader of the Renewed Church’s vision for the mission to the “heathen”. Zinzendorf drew this up after he had made his famous journey through Pennsylvania in 1742 and had already met with the major actors in the Colonial and Woodlands Indian world in this period of early contact. He was one of the first Europeans to traverse Susquehanna Country. In 1742, as he traveled from Bethlehem west via Tulpehocken (the home of Conrad Weiser), through to Harris’ Ferry (today, Harrisburg) and up the Susquehanna River. In his journal, Zinzendorf described this journey along the river with his companion, Anna Nitschmann and the others. On the second day of the journey, he writes, “We traveled on, and soon struck the lovely Susquehanna. Riding along its bank, we came to the boundary of Shamokin.” On Sept. 30 he describes the Susquehanna River as he makes his way up the West Branch to meet with Madame Montour at Ostonwakin, and then on to the Great Island. He writes “Set out on our journey. The Sachem (Shikellimy) pointed out the ford over the Susquehanna. The river here is much broader than the Delaware, the water beautifully transparent, and were it not for smooth rocks in its bed, it would be easily fordable. In crossing, we had therefore to pull up our horses and keep a tight rein. The high banks of American rivers render their passage on horseback extremely difficult.” As Zinzendorf rides through the forests that border the Susquehanna River he experiences his first Pennsylvania fall. “The country, through which we were now riding, although a wilderness, showed indications of extreme fertility. As soon as we left the path we trod on swampy ground, over which traveling on horseback was altogether impracticable. We halted half an hour while Conrad rode along the river in search of a ford. The foliage of the forest at this season of the year, blending all conceivable shades of green, red, and yellow, was truly gorgeous, and lent a richness to the landscape that would have charmed an artist. At times we wound through a continuous growth of diminutive oaks, reaching higher than our horses’ girth, in a perfect sea of scarlet, purple, and gold, bounded along the horizon by the gigantic evergreens of the forest.” The colors are rich and charming, the country is fertile, the trees exotically enormous. (All quotations are taken from “Count Zinzendorf’s Narrative of a Journey from Bethlehem to Shamokin, In September of 1742” in Wilhelm Reichel, ed., Memorials of the Moravian Church, vol. 1 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1870), pp. 85-93)

In 1742, Zinzendorf draws up a plan for proselytizing to the Indians. He focuses on five places where he knows both the Native leaders, Moravians and Europeans sympathetic to the plan who are already in the area, and the potential for these to belong to a structured world  of Moravian missions. As we can see from this plan, Bethlehem was considered to be the center of all mission activities, the place on which depends the direction of all the work in the areas around Bethlehem, the North River (or North Branch of the Susquehanna River), Shamokin at the confluence of the West and North branches of the Susquehanna and at Gnadenstadt, which was envisioned to be settled in the Wyoming Valley. Other places he outlines in this sketch for the mission structure are Ostonwakin, on the West Branch of the Susquehanna River, which consisted of three main villages of mixed Iroquois nations, led by the Montour family. This center of mission activity would allow the Moravians access to the Ohio river watershed and also a pathway, both literally and figuratively, to the council fire at Onondago of the Five Nations of the Iroquois. Shekomeko, in upstate New York, was already a Christian village and was to act as the base from which Mahican Christian Indians could be sent to form new mission villages; the Wyoming Valley on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River, which was inhabited by peaceful members of several Iroquois Nations, the Mohawks, Oneida, Onondago, and Cayuga was considered to be a fertile ground for cooperation between the Native peoples and the Moravian missionaries. Finally, the Mahican converts in Shekomeko were to proselytize in New England.

of Moravian missions. As we can see from this plan, Bethlehem was considered to be the center of all mission activities, the place on which depends the direction of all the work in the areas around Bethlehem, the North River (or North Branch of the Susquehanna River), Shamokin at the confluence of the West and North branches of the Susquehanna and at Gnadenstadt, which was envisioned to be settled in the Wyoming Valley. Other places he outlines in this sketch for the mission structure are Ostonwakin, on the West Branch of the Susquehanna River, which consisted of three main villages of mixed Iroquois nations, led by the Montour family. This center of mission activity would allow the Moravians access to the Ohio river watershed and also a pathway, both literally and figuratively, to the council fire at Onondago of the Five Nations of the Iroquois. Shekomeko, in upstate New York, was already a Christian village and was to act as the base from which Mahican Christian Indians could be sent to form new mission villages; the Wyoming Valley on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River, which was inhabited by peaceful members of several Iroquois Nations, the Mohawks, Oneida, Onondago, and Cayuga was considered to be a fertile ground for cooperation between the Native peoples and the Moravian missionaries. Finally, the Mahican converts in Shekomeko were to proselytize in New England.

Whereas some of these ambitious plans to organize the mission effort among the Native populations of the Woodlands Indians were realized, most notably the mission at Shamokin and that at Gnadenhütten, the outbreak of the French-‐Indian war had an immediate effect upon the possibility of Native converts living close to or even among any white congregation. The mission at Shamokin was abandoned in 1755 and soon after, Gnadenhütten was razed to the ground. But even as the increase in racial tension between Euro and Native Americans reached new levels around Bethlehem and Nazareth in the two years that followed these attacks, the decision was approved by Lot in Herrnhut to begin the enterprise of establishing an Indian village in the vicinity of Bethlehem. The argument was that this was in accordance with Zinzendorf’s plan, outlined above in the “Heiden Collegia”. However, 1757 was not 1742 in the Middle Colonies. What might have been perceived as a possibility in the still relatively peaceful earlier era of white settlement, where the Native population was regularly included in the conferences and treaties of the Colonial government on almost an equal footing, in accordance with the utopian vision of the pacifist Quaker William Penn, now flowed almost perversely against the tide of racial separation, suspicion and fear that marked the rivers and valleys of Pennsylvania.

In addition, as Brother Martin Mack argued, Zinzendorf’s plan showed no awareness of the cultural needs of Native people to have good hunting grounds close to their settlements. The Indian villages of the converted Moravians were planned out following a European model with kitchen gardens, domestic animals, and separate family houses. Where would the inhabitants of an Indian village onthe Monocacy be able to hunt in an area of quite dense Euro-‐American settlement, traversed by the turnpikes that carried wagons of goods to and from Philadelphia, Lancaster, and Reading? Despite all these obstacles, the Native Americans who were living in Bethlehem, some of whom were residents of the destroyed or abandoned Indian towns listed in Zinzendorf’s original plan, agreed that the building of a town for them outside Bethlehem was desirable and so, with the permission of the Governor of Pennsylvania, the plan was approved. As Levering has discussed in his compendious history of Bethlehem, the construction of Nain had to be done also with the permission of the Iroquois and also the “Delaware King,” Teedyuscung, an erstwhile Moravian convert who now agitated against the Moravians and even accused them of holding the Moravian Indians hostage. Only with the permission of these two groups, the Governor argued, could the building of Nain proceed.

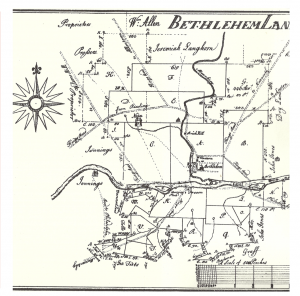

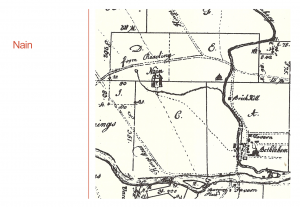

And proceed it did! Embracing several hundred acres of the best land in the region, on property owned by the wealthy Quaker Benezet family, the place that had already been given the name of Nain by Zinzendorf was cleared. Providing Bethlehem with firewood for the winter of 1757-‐8 the land that was being cleared was perilously close to the Reading-‐Easton turnpike and there were fears that this proximity could lead to an escalation in the racially motivated attacks by whites on the Moravian Indians. Mutual suspicion was running high and the Moravian Indians were assured of protection by the Governor and the Bethlehem inhabitants. Teedyuscung decided to spend the winter on the south side of Bethlehem, to keep on eye on the Moravian Indians and the building of Nain.

So, beginning in the cold winter of 1758 the lumber and fence rails of the new settlement were prepared, the site for new buildings selected. The Native Americans living in neighboring Gnadenthal offered to help with the construction work, the town was staked out, and the work progressed nicely into the spring months. As the village was being built, land was also being prepared for growing crops. By the end of May the fence around the village was finished, the first house was blocked up in June, and the building of houses, some from the lumber of the former Bethlehem chapel, continued on throughout the summer. The new chapel was built, and services of dedication conducted on October 18. Services were conducted bilingually, sometimes tri-‐lingually in Mahican, Delaware and German. Children’s services were held, the Gemeinhaus was built and a house erected for the unmarried missionary. There were 90 Indians present at the dedication service for the chapel and by 1762 there were 14 houses and four huts in the village. The village flourished, crops grew and were harvested, the was an abundance of venison around the end of the first year. All seemed to be going as planned! The missionaries working in Nain, Brothers Schmick, Martin Mack (1758-‐59) and Grube., were all experienced missionaries who had lived with and labored among many of the Indians who lived in the village. The Sprecher of Nain was the Mohican, Josua, Sr. a member of the Wolf clan. The diaries of the mission village reveal a life that centered around the services and liturgical life of many other Gemeinen . Visitors from Bethlehem would come regularly to speak with the choir members of the single brethren, single women, married men and women and widowers and widows. Sister Lawatsch speaks with deep affection of the village on her deathbed in 1760 where she remembers her visits to Nain during the harvest love feast the previous year and asks that she be remembered to them and remind them of her love for the Savior. In the second year of its existence, a house for the Single Brethren was dedicated, as was the Gottesacker. The village slowly expanded, necessitating the building of a new chapel by 1763. Liturgical life was little different from that of the non-‐Indian Gemeine across the Monocacy Creek. Devotional paintings depicting Christ’s life were displayed in the chapel, festival days were marked by trombone choirs, scriptures were read, hymns were sung, lovefeasts celebrated, in Mahican, some in Delaware and some in German.

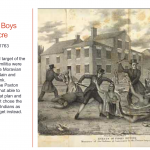

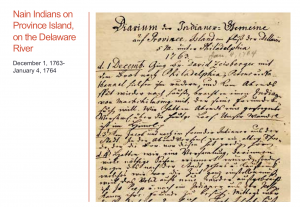

But this protected existence could not last. Nain village was under the constant surveillance of its white neighbors for signs of drunkenness, unlicensed gunpowder sales, and any other expected infractions of order. This suspicion and hostility increased for the next three years until in December 1763 the infamous Scots-‐Irish Paxton Boys attacked and brutally murdered the peaceable Susquehannock Indians who were still living in Conestoga manor, land granted to the few remaining Susquehannock Indians by the Penn family. The perpetrators of the massacre defended their actions in a remonstrance published in 1764, claiming that the violations of the “distressed and bleeding” frontier were an affront to the brethren and relatives of the murdered whites. It is thought that the Paxton boys actually fell on the Conestoga Indians only after repeated attempts to massacre the Moravian Indians had been thwarted. They accused the Moravian Indians of Nain as sending messages to the Shawnee living on the Great Island to plot further murders of the white settlers along the Susquehanna River. According to Kevin Kenny, the Paxton Boys were not the only ones to suspect that the Indians of Nain were secretly trading with enemy Indians and supplying them with guns and ammunition. The Assembly’s commissioners also believed that “there is much reason to suspect the said Moravian Indians have also been principally concerned in the late Murders committed near Bethlehem, in the county of Northampton” (Kevin Kenny,God’s Peaceable Kingdom, p. 133) In response to these accusations, in October 1763 restrictions were placed on purchases of gunpowder in Nain, and the commissioners recommended that the Nain Indians be removed to Philadelphia so that their “behavior may be more closely observed.” (ibid.) To this end, on November 8 1763 a party of 127 Indians from the missions of Nain, Wechquetank, Nazareth and Bethlehem set out for Philadelphia. How did the non-‐Indian residents of Bethlehem view the departure of the Indians, not only from the mission villages but also from within the very choir houses of Bethlehem itself? Kate Carte Engel has argued that the removal of the Nain and Wechquetank Indians was something accepted by the Bethlehem non-‐Indian residents and that they did not fight this decision because they had never seen them as part of their community (Engel,  , p. 184) In some ways this might be true, but the removal of the Indians from Nain and Wechquetank and Bethlehem probably did save their lives. For merely a few weeks after the Moravian Indians arrived in Philadelphia on November 11, greeted by a furious mob ready to murder them, the Paxton Boys murdered the Conestoga Indians. Afraid that the Philadelphia barracks would not protect them from the mob, the Moravian Indians were moved to a former “pestilence house” on Province Island in the Delaware river. And there they stayed for fifteen months. Conditions were terrible in the prison. Disease was rampant. By the end of 1764, 56 of the Indians had died, nearly half of them children.

, p. 184) In some ways this might be true, but the removal of the Indians from Nain and Wechquetank and Bethlehem probably did save their lives. For merely a few weeks after the Moravian Indians arrived in Philadelphia on November 11, greeted by a furious mob ready to murder them, the Paxton Boys murdered the Conestoga Indians. Afraid that the Philadelphia barracks would not protect them from the mob, the Moravian Indians were moved to a former “pestilence house” on Province Island in the Delaware river. And there they stayed for fifteen months. Conditions were terrible in the prison. Disease was rampant. By the end of 1764, 56 of the Indians had died, nearly half of them children.

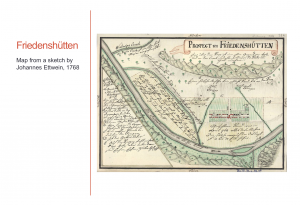

The fate of the Nain Indians in the Philadelphia barracks was a constant source of concern for the Bethlehem Moravians. Given the political unrest and racial hatred now rampant in the Pennsylvania backcountry, that was spilling into the crowds of the cities of Philadelphia and Lancaster, it was clear that Nain could no longer be the home of Christian Indians. In September of 1764, before even a clear decision had been made as to the fate of the Nain Indians, plans were drawn up to dismantle the buildings in the village across the Monocacy. After the leaders of the Indians in the barracks petitioned for their own release, they were permitted to leave the city and arrived on March 22 1765 back in Bethlehem in deep snow. They were allowed to briefly stop for a week at what remained of their old homes. Six of the fourteen houses were sold to individuals in Bethlehem on March 30, (according to Levering, one was the chapel) and then the following day a farewell lovefeast was held and on April 3 the Indians left Bethlehem for Friedenshütten.

Kate Carte Engel has argued that the end of Nain marks the end of the original mission of Bethlehem. (Engel, p. 195) That might be true in a limited sense, in that Zinzendorf’s original plan which was drawn up in the early days of Moravian presence in the colonies was now clearly no longer operative. However, it is not true that Moravians were no longer working closely with Native peoples. As we know, David Zeisberger and Johannes Ettwein led the families of Nain, after their seven year sojourn in Friedenshütten on the North Branch of the Susquehanna to Ohio, to found another Gnadenhütten, and then up into the territories around the Huron River. The mission of the Moravians to the Native peoples of North America continued well into the 20th century. What had changed however significantly was the possibility that this vision for “a collegium of the converted” would be in any way congruent with the politics of the New Republic. The massacre at Gnadenhütten. Ohio in March 1782 of around 100 Moravian Indians, many of whom were either related to the Nain Indians or had actually lived there, was in many ways an inevitable and logical escalation of the racially motivated frontier violence that had been witnessed in 1763 in Conestoga and which prompted the interning of the Nain Indians in Philadelphia. The Moravian work among the Native peoples, motivated by a belief that all men and women regardless of race and culture possess a soul that can be ignited for Jesus, became an anomaly in an increasingly binary world of white versus other. In most Native eyes, especially those of the Delaware, Mohicans, and Iroquois, Moravians were considered to be figures of trust, people who took the time to learn their languages, to understand their culture, who respected their worldviews and cosmologies, even if it was with the goal of translating those notions of orenda or Manitou into Moravian Christian concepts of the Holy Spirit as Mother and Christ as the sacrificial Lamb. As scholars such as Jane Merritt have pointed out, the painted scenes of the Passion, the bloody language of the Litanies and hymns were not necessarily that foreign to the Native peoples. in fact the infamous Litany of the Wounds was the most popular litany among the Moravian Indians and records show that as late as 1758 services in Nain were strongly emphasizing sifting period language. But this desire for conversion to Christian faith through the achievement of an individual understanding of salvation became a “third way” in the history of the settling of the United States. As U Penn historian Daniel Richter has described it, the Moravian “experiment” did not fit within the binary structures of racial politics and expansionist thrusts that were the hallmarks of American history of the 19th centuries.

At the beginning of my talk, I suggested that the dedication of the Nain house offers the interpreters of Bethlehem history an opportunity to enter into a new phase of public education. I would like to urge the wonderful societies represented here and the organizations that worked so hard to see this project come to fruition to put behind us the era of Moravian historiography that in 1956 painted a picture of the Nain Indians as passive, powerless and victimized peoples, whom the Moravians taught “thrift and self-‐dependence” and who signed for their wages with “drawings of their totems, .. quaint momentos preserved in the Moravian Archives.” (Elma Gray, Wilderness Christians, 1956) In my work on the Moravian Indian village of Friedenshütten to which the Nain Indains moved in 1765 after leaving Bethlehem, I have come into contact with many Native American groups among the Haudensosaunee; Seneca, Tuscarora, Mohawk, Onondago, who want to know more about this vital part of their own history. The Moravian records reveal details of their forebears’ lives that are preserved nowhere else, they record the words and deeds of those who otherwise have passed into the anonymity of the defeated in history. And I would urge us to work to rebuild those bonds of friendship that were forged by the first Moravian missionaries who set out from Bethlehem over 250 years ago. Thank you!